Learn About New York City's African-American History

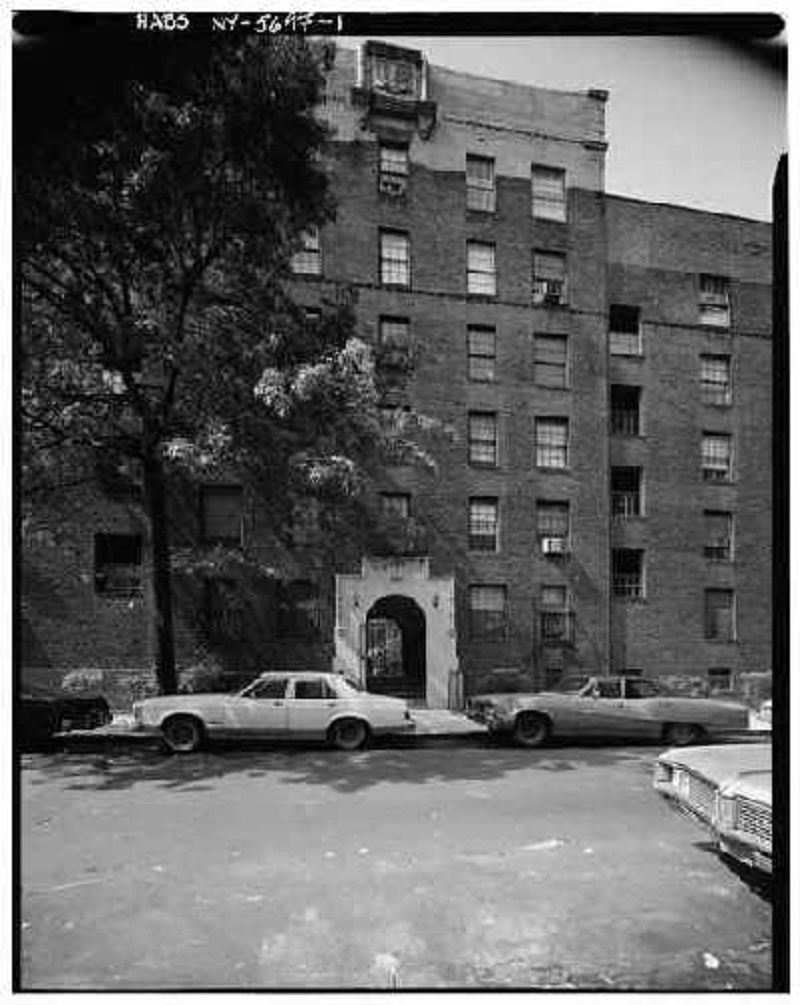

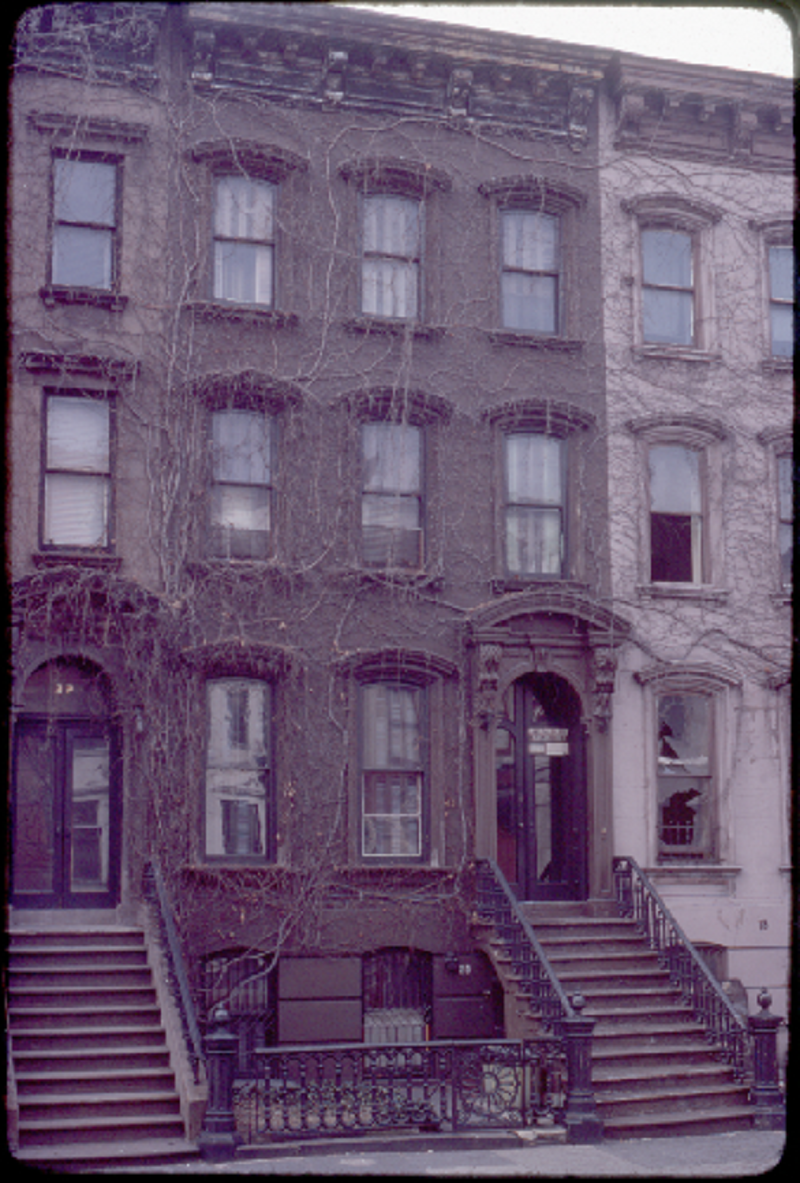

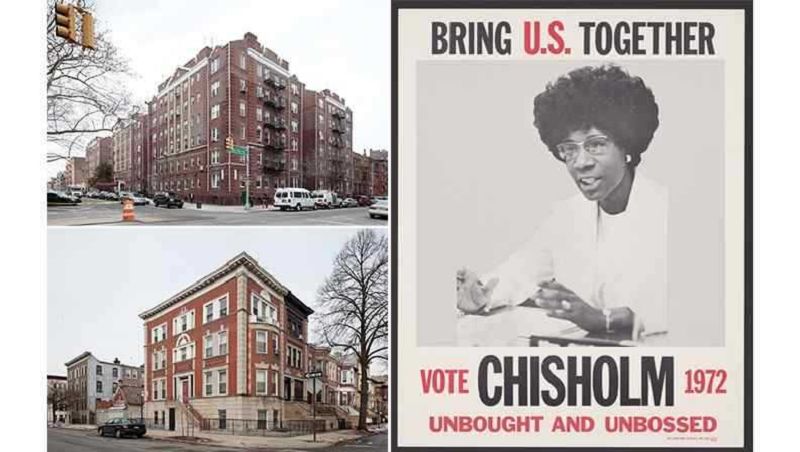

Born in Bedford-Stuyvesant to Caribbean immigrant parents, Shirley Chisholm moved to 1094 Prospect Place in the Crown Heights North III Historic District with her parents in 1945, when she was in her early 20s. At the time, this neighborhood, with its hundreds of distinguished houses and apartment buildings constructed in the Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, and other popular late-19th and early-20th-century styles, was becoming one of the city’s largest and most prominent African- and Caribbean-American communities.

Born in Bedford-Stuyvesant to Caribbean immigrant parents, Shirley Chisholm moved to 1094 Prospect Place in the Crown Heights North III Historic District with her parents in 1945, when she was in her early 20s. At the time, this neighborhood, with its hundreds of distinguished houses and apartment buildings constructed in the Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, and other popular late-19th and early-20th-century styles, was becoming one of the city’s largest and most prominent African- and Caribbean-American communities.

Image, right: Billie Holiday, ca. Feb 1947, Library of Congress

Image, right: Billie Holiday, ca. Feb 1947, Library of Congress